It’s a remedy to the modern road course. A return to racing circuit greatness by combining some of the greatest corners out there. And it exists only in my imagination.

No, I’m not the first person to piece together a fantasy racetrack from existing elements. Formula 1 drivers including Max Verstappen and Daniel Ricciardo have endeavored this exercise, collectively combining many of the same components, including Eau Rouge at Spa, the Esses at Suzuka, and the uphill first turn in Austin.

There are even a few real-world circuits that took inspiration from – or directly copied – corners from other tracks. Pocono Raceway designed its three turns after Trenton, Indianapolis, and Milwaukee. Circuit of the Americas has sections modeled after Silverstone, Interlagos, Hockenheim, and Istanbul. And the never-raced Hanoi street circuit drew inspiration from the Nürburgring, Monaco, Sepang and Suzuka.

My own design takes pieces from some of these famous F1 venues, but also pulls from classic North American road courses and global endurance circuits. And ultimately, if someone ever constructed this track either in the real world or the sim world, I’d imagine that sports car and endurance racing — not high-level open-wheeled competition — would be its calling.

The Circuit Stats

This circuit combines 14 sections from different tracks, ranging from straightaways to corners to the elevation changes that make them unique.

The total length adds up to 5.05 miles or 8.13 kilometers. That makes it 16% longer than Spa, the longest current F1 track, and on par with Thunderhill Raceway Park in California, where the nearly 5-mile combined circuit hosts a 25-hour endurance race each December.

From the highest point in turn 8 to the lowest point entering turn 17, the circuit features 124 feet or 38 meters of elevation change. But elevation isn’t all it offers.

Despite its patchwork nature, each of the three sectors includes some similar elements. The first is mostly flat, with corners progressively getting tighter and slower through the stadium-style turn 5. The second sector features most of the undulation, initially climbing and then falling through separate sets of high-speed esses. And the final sector is all about speed, with five separate straightaways that each terminate in a passing zone.

That variability would demand a compromise in car setup and would challenge drivers through the full range of their skill sets, along with their physical conditioning.

It’s a mental test as well, since unlike modern circuits, you won’t find acres of paved runoff surrounding this track. Instead, errant cars may grind to a halt in gravel traps, or be punished even worse by the barriers that border many corners.

That makes aggression a risk while patience and consistency are rewarded. And given my own measured driving style and strength in endurance events, I don’t think my dream circuit could have it any other way.

Start/Finish to Turn 1 – from Road America

Section Length: 0.38 miles/0.60 kilometers

Net Elevation Change: -2 feet

A lap starts on my favorite frontstretch in motorsports. While we don’t make the gravity-defying uphill climb to the start/finish line at Road America, we begin at the crest of the hill and make a nearly 2,000-foot run down to the first corner.

Its trickiness stems from its simplicity. There are no kinks in the road, bumps in the braking zone, or Tilke-esque widening of the track to enable divebombs up the inside. Instead, it’s a straight shot into a bottleneck corner, and you can see it coming from nearly half a mile away.

That acts to build anticipation, whether you’re on a hot lap preparing for the first make-or-break corner, or in a side-by-side battle waiting to see who brakes later.

My own experience at Road America includes draft battles and breakaways in the Spec Racer Ford. The high speeds down the frontstretch at my circuit would promote a similar sort of tactical racing, culminating with the flat but fast entry to turn 1.

Turn 1 Apex to Exit – from Montreal turn 7

Section Length: 0.28 miles/0.45 kilometers

Net Elevation Change: +11 feet

While turn 1 at Road America opens up a bit on exit, at my track, it keeps getting tighter. To enable that, I have stamped it with the exit of the second chicane at Circuit Gilles Villeneuve.

It’s a deceivingly long, winding corner, and for over-eager drivers who track out too early, they’ll find an unpleasant surprise awaiting them just past the exit kerbing, as described by former F1 driver and current Sky Sports commentator Anthony Davidson:

“But a driver must still be careful here because there’s a wall on the outside of Seven and we’ve seen in the past how running wide… can have the knock-on effect of putting a car either close to or into the wall.”

For dueling drivers, this turn creates an obvious pressure point and potentially for excitement. Holding the outside line puts you closer to the wall on exit but could help carry more speed down the following waterfront short chute.

Meanwhile, going fast enough up the inside could help you complete a pass by mid-corner, but if you’re not fully in front, you’ll have to check your speed and watch for wheelspin as a side-by-side fight continues into the next section.

Turns 2 and 3 – from Sebring turns 12 and 13 (Tower)

Section Length: 0.36 miles/0.57 kilometers

Net Elevation Change: -5 feet

Moving out of the claustrophobic armco-lined straight, the track now opens up in my favorite sequence of corners from one of my favorite endurance racing circuits, the Sebring International Raceway.

We begin with the wide, fast turn-12 kink. Given the lack of braking required here, it barely qualifies as a corner, and yet in some situations, it can be even more important than the turn that follows.

When defending a position, holding a middle to inside line can cut off any passing opportunities for the driver behind by forcing them on the longer, marble-littered outside line.

When attempting a pass, making an early move up the inside of Sebring’s turn 12 can set up a braking-zone dive into turn 13.

And when faster-class traffic approaches through this section, the same car positioning rules apply to averting or facilitating a pass.

Turn 13, or Tower corner, has the sort of uninspiring blueprint you’d expect of a 90-degree turn plucked from a flat airport circuit, but in practice, it’s a great challenge behind the wheel.

The raised inside kerbing limits how much you can cut the corner. Its profile and the straight that follows demand a later apex, which means driving in deep and turning in late. And the flat outside exit kerbs are flanked by grass and dirt, which gives limited room for running wide.

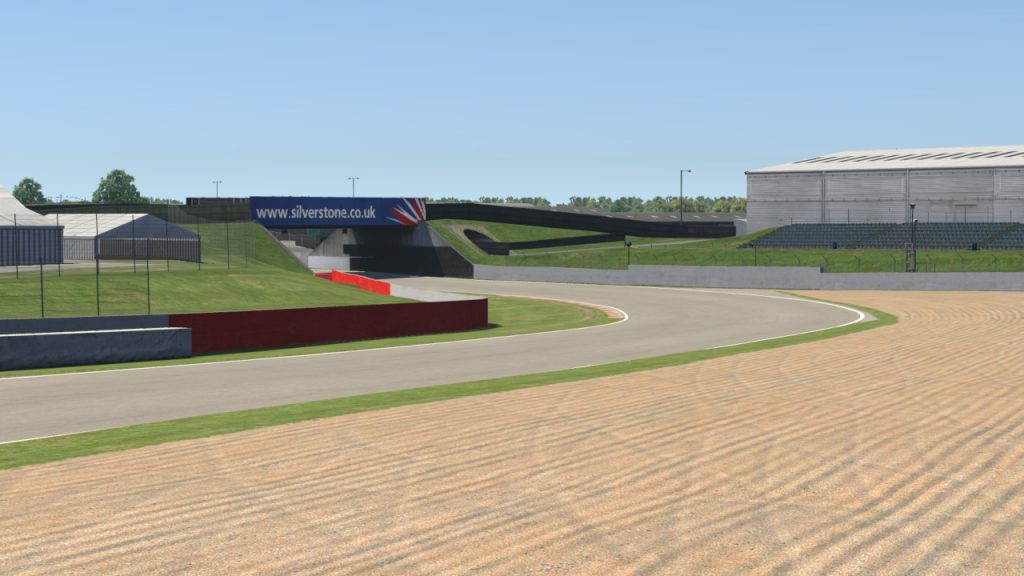

Turn 4 – from old Silverstone turn 13 (Bridge)

Section Length: 0.19 miles/0.31 kilometers

Net Elevation Change: +5 feet

Consider this corner an act of altruism, righting a wrong in the recent history of race track renovation. When Silverstone was reconfigured in 2010, the technical new infield layout bypassed one of the circuit’s most iconic sections at Bridge corner.

At this airfield circuit, it was a rare corner with elevation, as the track exited the Abbey chicane, then dove downhill under the namesake roadway bridge before climbing on exit.

For bold drivers, it presented a passing opportunity, as I found during a three-hour Blancpain Endurance Series race in 2015. On the final lap, I made a move through Bridge to get by a fuel-starved BMW and steal a twelfth-place finish in our highly competitive split.

Perhaps that sort of move was a fulfillment of Martin Brundle’s prophesy about the corner when it was added to the circuit in 1991:

“It looks like an enormously quick corner, slightly banked as well; that’s where I’m going to buy a ticket for when I come and watch! There’ll be a few brave souls trying to overtake on the way in, which will be interesting, and if you get it right on the way out you should be able to overtake into the next left-hander.”

While Bridge’s place on the Silverstone grand prix layout lasted only two decades, it will live on at my circuit. And Brundle would be proud, as my Bridge replica exits into a grandstand-lined section where fans can watch those overtakes happen.

Turn 5 – from Hockenheim turn 12 (Sachs-Kurve)

Section Length: 0.15 miles/0.24 kilometers

Net Elevation Change: +3 feet

The Hockenheimring has seen its own changes over the years, notably neutering the long straightways that ran through the forests and replacing them with much slower chicanes and hairpins.

But one element of the old circuit remains: the stadium section near the end of the lap that wraps around the unique turn 12.

Even driving old F1 video games as a kid, it was a corner in which I felt at home. As a slightly banked left-hander, it could have been taken from the short tracks at Martinsville or Hickory, rather than resting in the Rhineland thousands of miles away.

When Hockenheim landed on iRacing last year, I found equal comfort in this corner. Searching for my first official-series victory in more than two years, I used a last-lap pass through turn 12 to take the lead and the win in a Porsche Cup race.

In that case, it was a corner of opportunity, but it can also be a corner of misfortune. It’s tempting to overdrive the entry and take advantage of the banking support, but pushing too hard can still send your car wide, as Sebastian Vettel found while leading the 2018 German Grand Prix.

Add in the expectant gazes from thousands of fans seated around the hairpin, and it’s simply a must-have on my own dream circuit.

Turns 6 and 7 – from the Nürburgring turns 9 and 10 (Michael-Schumacher-S)

Section Length: 0.26 miles/0.42 kilometers

Net Elevation Change: +91 feet

As the first sector ends and the second begins, we start our uphill climb with a copy of the Nürburgring’s Schumacher S.

The quick left-right sequence may be trivially flat-out for modern Formula 1 machinery, but in a GT car, it’s still a daring thrill that requires minimal braking, precise turning, and a bit of bravery even in a sim to carry speed over the kerbs as the track crests 91 feet higher than where this section began.

Along with the excitement of these climbing corners, I include this section because I’ve always been pretty good at it. When my teammate Karl and I were preparing for a league endurance race in the temperamental Ruf C-Spec a few years ago, I was a half-tenth or more faster in this section, even if I lost time elsewhere in the lap.

In that case, I was braking earlier but getting back to the throttle sooner and carrying up to 4.4 km/hr more speed off the corner and down the short straightaway that followed.

It’s an approach that required confidence in throttle application and a steady wheel, since accelerating too soon could send the back wheels sliding or the car careening off the road entirely.

But for a complex named after the legendary Michael Schumacher, would you expect it should require anything but precision?

Turn 8 – from VIR turn 10 (South Bend)

Section Length: 0.16 miles/0.26 kilometers

Net Elevation Change: -7 feet

This is the lone corner on my dream circuit that I’ve actually driven in real life, and I can confirm that it does drive like a dream.

The final turn of the Climbing Esses sequence, the road rises to a crest – and my circuit’s highest point – mid-corner before falling away on exit. Driving in too deep or tracking out too wide is almost always punished with a trip through the grass.

My first encounter with this corner came at the Bertil Roos Racing School, which my dad and I attended in June 2007. Our instructors had advised making a moderate lift on entry here, and while watching early groups of drivers on track, I saw several run wide, which gave me a healthy respect for this challenging corner.

After taking to the track myself, I quickly got the hang of it, and by our second session of the day, I was attacking it full-throttle almost every lap. While that’s probably no great feat in those underpowered cars, for my first time driving any car on a real racing circuit, it felt like a nice accomplishment to muster the courage to keep my foot to the floorboard through that fairly blind corner.

My dad and I returned to VIR nine years later, this time for charity laps in my Honda S2000. As I previously wrote, that paced session felt more like an open track for hot-lapping, and my sports car felt especially at home through the Climbing Esses.

I’ll take those experiences as a sign of confidence and a stamp of approval. South Bend, welcome to my fantasy circuit.

Turn 9 – from the Nordschleife (Aremberg)

Section Length: 0.27 miles/0.44 kilometers

Net Elevation Change: -51 feet

We’re back to Germany for the next corner, and this time, it’s taken from the longest circuit of them all: the Green Hell, or the Nürburgring Nordschleife.

Simply learning that track and its 154 corners took me several weeks, and while initially orienting myself, Aremberg corner – at the northwestern edge of the circuit – served as a useful reference point.

It was also one of the first corners through which I felt comfortable driving. Like Hockenheim’s stadium hairpin, perhaps the camber to the road suited my oval-racing background, even if Aremberg is turning right instead of left.

It’s a tricky turn for sure, with the road falling away throughout the corner, and any excess speed not easily scrubbed off without running into the gravel trap or the outside wall.

My approach has always been to take a wider entry, then fade to the inside while letting the banking support the car and guide it through to the downhill exit.

With a Nürburgring 24 Hour class win to my name, it seems I’ve done something right at Aremberg, and this fun corner deserves a spot on my circuit.

Turns 10 and 11 – from Road Atlanta turns 4 and 5 (The Esses)

Section Length: 0.42 miles/0.68 kilometers

Net Elevation Change: +9 feet

Exiting my Aremberg copy, the descent continues through Road Atlanta’s Esses. The overall Road Atlanta circuit may just surpass Sebring as my favorite for multi-class racing, and one big reason is this section, where well-timed passes are possible, but patience is often a virtue for faster cars.

This is a roller coaster-like set of corners that I’d love to try in real life sometime. Each turn is tighter than the one before it, beginning with a gentle left-hander, followed by a plunging reversal to the right, then a subtle left-right slither as the road begins to rise up again.

Negotiating this sequence so far is generally possible full-throttle, assuming you adhere to the optimal line and don’t get guided astray by an over-optimistic prototype or – as I found during the closing hours of last year’s Petit Le Mans – a lack of illumination that sent me a few feet off line.

But the hardest part of this section awaits at the very end: a sudden, uphill jog to the left that demands carrying as much speed as possible to connect the esses with the straightaway that follows. The ample exit kerbing is tempting to use, but it can easily cause a car to bottom out and go sliding into the outside wall, or back across the track in front of traffic.

Because of that risk, successfully getting through this corner hundreds of times in an endurance race often requires a bit of caution, or pushing to only 90 or 95% of the limit. But qualifying here means leaving nothing on the table, and that makes this section especially exciting.

In fact, my self-described best drive ever was during a qualifying session for the NEO Endurance Series’ season-one finale. During my final run, with a bit of extra downforce onboard to better negotiate these snaking corners, I gained time through The Esses and carried it through the rest of the lap to land in fifth place on the starting grid.

It’s the only time I can remember trembling after getting out of a virtual car, having pushed as hard as I could to log a fast lap. Including this section from Road Atlanta on my own circuit will make sure that lap, and that feeling, will never be forgotten.

Turn 12 – from Belle Isle turn 3

Section Length: 0.35 miles/0.57 kilometers

Net Elevation Change: 0 feet

Having completed the undulating second sector, hopefully with the car still in one piece, we now begin the track’s long, fast final sector. It starts with a street circuit feeling, taken from Detroit’s Belle Isle course.

The bumpy, wall-lined exit of Belle Isle’s turn 2 has caught plenty of drivers – even in pace cars – by surprise over the years. Forgivingly, my circuit will join just past that trouble spot on the straightaway down to turn 3. But the bumps aren’t finished yet.

They pick up again on the approach to turn 3, and picking the right braking point using the markerboards on the fence can be challenging while your car is bouncing over the bumps.

In addition, the ideal entry to this corner requires keeping your car as far left as possible, often millimeters away from brushing the concrete wall.

Getting through the turn means taking a generous amount of the inside kerbing and using the narrow exit kerbs without running too wide into the grass – or the wall.

The long straightaway leading up to it also makes this turn a passing opportunity, but spotting your braking point while racing side-by-side with another car adds to the challenge.

My iRacing career includes two visits to this venue: first in the Formula Renault 2.0, then in the Porsche Cup series, which included a pass around the outside of turn 3. Both of those experiences left me wanting more from Belle Isle, so I’ll take a piece of it – bumps, walls, and all – for my dream circuit.

Turn 13 – from Le Mans (Arnage)

Section Length: 0.58 miles/0.93 kilometers

Net Elevation Change: -10 feet

The Circuit de la Sarthe in Le Mans, France, is famous for its long straightaways and fast, sweeping corners. But for my circuit, I chose one of Le Mans’ slowest turns, which is also one of the most important, both on the original circuit and on mine.

The section including Indianapolis and Arnage contains three corners, each slower than the one before it. First, there’s the high-speed kink leading into a braking zone. Then comes the banked Indianapolis corner. Finally is the tight right-hander called Arnage.

It’s one of the oldest corners at Le Mans, dating back to the 1921 layout with few changes since then. One big reason for its historical stability is the presence of a house just outside the corner that has limited any modifications, such as adding runoff areas.

That changed slightly in 2012, when a gravel trap was added and the outside wall was pushed back by a few feet, but Arnage still leaves little room for error. Take it from five-time Le Mans class winner Oliver Gavin:

“Arnage is the most frustrating corner on the circuit. It’s very slippery, very slow, and you feel that the car has almost come to a stop because you’ve been going so fast on the rest of the track. You can lose a lot of time in Arnage, and drivers frequently go off there. Unless you maintain 100 percent concentration, it’s very easy to make a big mistake in Arnage at some point in the race.”

Adding to the demands of Arnage is the long straightaway that follows, taking public roads all the way to the Porsche Curves. My circuit will detour before that point, but getting a good run off this slow, slippery turn will still be imperative.

Turns 14 to 16 – from Bathurst turn 20 to 22 (The Chase)

Section Length: 0.53 miles/0.85 kilometers

Net Elevation Change: -64 feet

My perfect circuit wouldn’t be complete without taking a piece of my favorite real-world track, the Mount Panorama Circuit in Bathurst, Australia. It’s probably no surprise that my own design shares several similarities with Bathurst, including its straightaways connected by slow corners, wall-lined sections with little runoff, and hilltop esses.

Frankly, I could have included almost any of Bathurst’s turns and had them fit with my circuit’s character, but I eventually settled on the section called The Chase, largely to serve a similar purpose on my own track: to break up a long straightaway with something more exciting than a basic chicane.

Funny enough, The Chase was viewed as exactly that when it was first added in 1987: “As for the chicane – if you want to call it that,” said Formula 1 champion Denny Hulme, “I wished it was never there.”

In the 35 years since then, it has proven its worth as a test of skill, as a passing opportunity, and even as a launching ramp for some incredible crashes.

While carnage on the mountain is often unavoidable when racing at Bathurst, I’ve always prided myself in being consistent and clean through The Chase, whether that was grinding to 5,000 road iRating using passes around the outside, pushing the limits in an eighth-place qualifying run for the 2019 Bathurst 1000, or clawing back lost positions in this year’s Bathurst 12 Hour.

And it’s one corner that neither Karl nor I can brag about being faster than the other. During our extended final practice session for this year’s 12-hour race, our average fast laps were exactly tied through The Chase section, down to the thousandth of a second.

That’s surely a sign of a couple of well-practiced and well-acquainted drivers with Australia’s fastest chicane.

Turn 17 – from Watkins Glen turn 10

Section Length: 0.23 miles/0.37 kilometers

Net Elevation Change: +10 feet

I often describe Watkins Glen as my first favorite road course, since in the early NASCAR Racing games, it’s the first one I took the time to learn and love.

While tracks like Montreal, Road Atlanta, and Bathurst later supplanted it atop my list, Watkins Glen is still a special circuit to me.

In part, that’s because of my own sim racing success there, including five wins in six POWER Series events. During those league races over the years, Watkins Glen became the only track where I was disappointed by anything less than a win.

In addition, it’s a fast track with a great flow, even for downforce-limited stock cars and sports cars. Patrick Long notes that in a GT3 Porsche, you need to keep some throttle application throughout the entire corner.

The penultimate corner on my own circuit is also the next-to-last in a lap around Watkins Glen. The fast left-hander at turn 10 includes a bit of camber mid-corner that flattens out on exit.

While the modern Watkins Glen circuit has generous paved runoff beyond the kerbing, a tidy exit here is important for the short straightway – and the final corner – that follows.

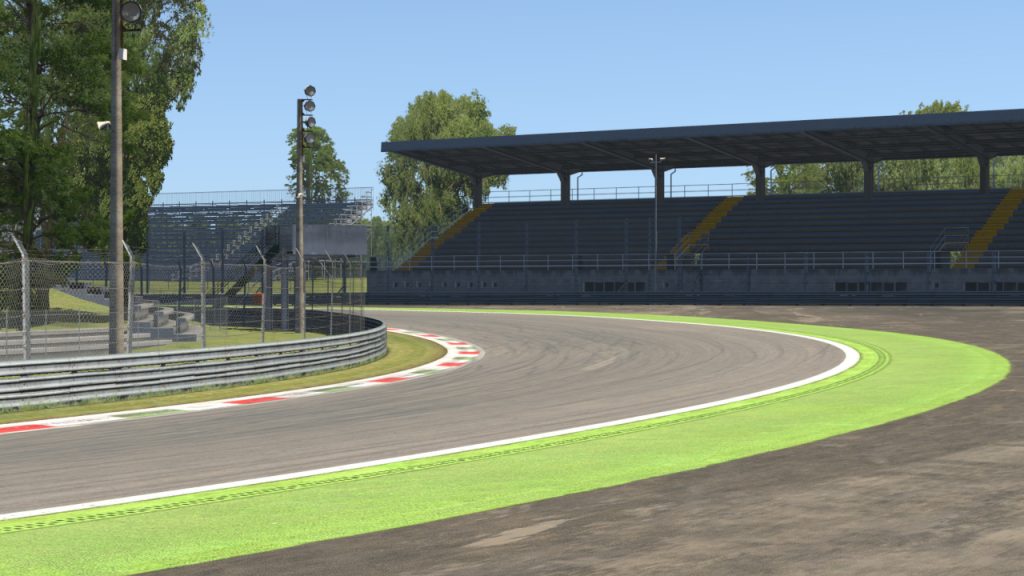

Turn 18 – from Monza’s turn 11 (Parabolica)

Section Length: 0.90 miles/1.45 kilometers

Net Elevation Change: +10 feet

Closing out my fast final sector is a clone of Monza’s Parabolica – a seemingly never-ending right-hander that unwinds onto my track’s longest straightaway.

As with many of my selections, one reason for choosing this corner was my own success here. In a Jetta draft battle against a faster opponent, it was the one corner where I had an advantage, helping me set up a late pass for the win and defend my position on the final lap.

It’s also a great way to end a lap: with a final legitimate passing opportunity that turns into a chance for a crossover on corner exit. It’s no coincidence that the closest finish in Formula 1 history happened at Monza. That 1971 result was facilitated by Peter Gethin’s pass into – and defense out of – Parabolica.

On my circuit, Parabolica is only the start of this final section. It continues down most of the Monza frontstretch, followed by the second half of Road America’s main straightaway. All together, that’s nearly a mile of flat-out driving from the final corner all the way to turn 1.

When locked in a battle, that would present plenty of time to draft, pass, and potentially defend against a re-pass attempt by an opponent. And for multi-class racing, it would give a Daytona-like run of on-throttle time to let faster cars pass en masse.

One thing is for sure, though: you better get Parabolica right, or you’ll have a long time to think about your mistake, probably while watching other cars speed past you down the frontstretch.

A Lap Around

A simulated onboard lap shows each of these 14 sections in their native habitats, but with a bit of editing magic, you can see how they might flow together, from the flat first sector through the rolling hills that follow to the high-speed ending.

A typical lap in a GT3 car would time in at around 2 minutes 50 seconds, with an average speed of about 107 miles per hour or 172 kilometers per hour. That’s somewhere in between the chicane-punctuated lap around Montreal and a speedier circuit of Road America – a fitting balance given the nature of my circuit, and the inspiration behind its design.

I’m sure I’ll never have the money or resources to literally move a mountain and build this track in the real world, and barring the release of a user-friendly track editor for iRacing, I doubt I’ll ever try it in the virtual world either.

But with many laps of experience through each of its sections, and plenty of great memories associated with them, I can imagine what it might be like to drive my perfect circuit — if only in my dreams.